1. McDonald’s Szechuan Sauce (1988)

In 1988, McDonald’s tried to cash in on the Disney craze with a limited-time Szechuan dipping sauce tied to the release of Mulan. The idea was to offer a tangy, Asian-inspired flavor alongside their Chicken McNuggets. But the promotion didn’t stick. Consumers found the taste underwhelming, and many didn’t understand the connection between McDonald’s and a historical Chinese legend.

The sauce quietly disappeared from menus, barely making a splash in sales. It wasn’t until decades later, when the animated show Rick and Morty joked about it, that people started to care. That irony alone shows how forgettable the original stunt really was. At the time, the fusion felt forced and too far removed from the brand’s usual flavor profile. While it technically flopped in the ’80s, it became one of the most bizarre McDonald’s footnotes in fast food history.

2. Burger King’s Herb the Nerd (1985)

Burger King’s 1985 campaign introduced America to “Herb,” a fictional nerd who had never tasted a Whopper. The goal was to turn Herb into a cultural phenomenon, complete with commercials, contests, and even sightings. Customers were told to find Herb in stores and say, “I’m not Herb” to win cash. It was confusing, awkward, and didn’t connect with customers at all.

The campaign bombed hard. Not only did people find the concept strange, but it also annoyed restaurant workers who had to deal with customers constantly repeating the catchphrase. The campaign wrapped within months, leaving the fast food giant with a multimillion-dollar loss and no memorable mascot to show for it. Experts later pointed to a lack of clarity in branding and storytelling. Consumers didn’t understand the joke, and without a solid emotional hook, Herb faded into marketing oblivion.

3. Wendy’s “Where’s the Beef?” Sequels (1984–1986)

Wendy’s struck marketing gold in 1984 with their “Where’s the Beef?” campaign. But instead of letting it shine, they milked the slogan too hard. Spinoff commercials, merchandise, and even a song followed. They even had 82-year-old Clara Peller appear in TV ads beyond Wendy’s, diluting the brand message. What started as a viral moment turned into a marketing overreach that quickly lost its flavor.

By 1986, Wendy’s had ended their relationship with Peller, and the campaign fizzled out. Analysts say the brand failed to pivot the catchphrase into a long-term identity. Instead of refreshing the concept or building deeper loyalty, Wendy’s banked too heavily on a single joke. Consumers moved on, and competitors caught up. The lesson? A great campaign can make you famous but overdoing it can make people forget why they loved you in the first place.

4. Domino’s “Avoid the Noid” (1986)

The Noid was Domino’s attempt to personify delivery delays as a villain. The red-suited, rabbit-eared cartoon character was everywhere in 1986, complete with TV ads and video games. But the campaign took a dark turn when a man named Kenneth Noid, believing the campaign was a personal attack, held Domino’s employees hostage at gunpoint. Although no one was harmed, the situation spooked the company.

The campaign was quickly pulled. While the Noid had gained some pop culture traction, the bizarre incident showed the risks of using real-sounding names in marketing. Experts now view the campaign as a cautionary tale about unintended consequences. Despite attempts to revive the Noid in later years, the original rollout is mostly remembered for how badly it unraveled. It’s a reminder that even clever ideas can be overshadowed by real-life chaos.

5. McDLT: “Keep the Hot Side Hot” (1984)

McDonald’s launched the McDLT in 1984 with a novel idea. It came in a double-compartment Styrofoam container. One side kept the patty hot, the other kept the lettuce and tomato cool. It was all about fresh appeal, but the bulky packaging felt excessive. Customers found it wasteful, and environmentalists were outraged by the extra foam.

The backlash gained momentum, especially as environmental concerns grew in the late ’80s. The packaging was seen as unnecessary and tone-deaf, and the McDLT was quietly pulled. Today, it’s studied as an example of good product intention with poor ecological timing. The sandwich itself wasn’t the problem. It was the message and materials. Fast food packaging has since come a long way, but the McDLT remains a frozen-in-time reminder that convenience can’t come at the planet’s expense.

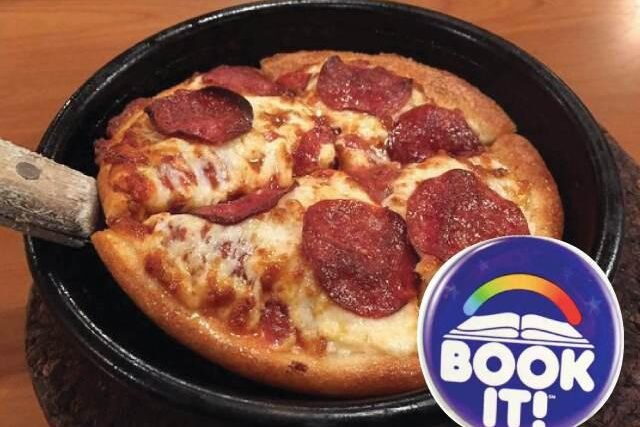

6. Pizza Hut’s “Book It!” Reading Rewards (1984)

In 1984, Pizza Hut launched “Book It!”, a program that promised free personal pan pizzas to kids who met monthly reading goals. Schools signed up, teachers tracked progress, and children eagerly devoured both books and thin crusts. On paper, it seemed brilliant. Boost literacy while selling pizza. In reality, educators and parents criticized the message that food rewards were tied to academic achievement.

Despite early enthusiasm, participation waned. Studies later suggested that extrinsic rewards can undermine intrinsic motivation, and health advocates argued childhood obesity concerns clashed with pizza incentives. Although Book It! still exists today, its scope and messaging have shifted to emphasize balanced meals and optional fruit sides. What began as a feel-good promotion revealed the pitfalls of rewarding education with junk food, prompting brands to rethink how to tie products to youth achievement.

7. Taco Bell’s “Emperor’s Club Card” (1987)

Taco Bell introduced the “Emperor’s Club Card,” a golden VIP card promising free tacos for life, to 1,000 customers who responded to mail-in ads. Holders felt elite, and Taco Bell hoped word-of-mouth hype would skyrocket visits. But too many people joined, and the chain quickly realized it couldn’t sustain unlimited free tacos.

Within months, the program was canceled, leaving cardholders disappointed and tainting brand loyalty. The backlash taught Taco Bell a hard lesson about overpromising. Marketing experts note that scarcity must be genuine. When exclusive perks flood the market, they lose value and frustrate customers. Today, Taco Bell uses digital loyalty apps with point-based rewards to control cost and engagement. The Emperor’s Club Card remains a cautionary tale. Exclusivity only works when it’s truly exclusive and economically viable.

8. Arby’s “We Have the Meats” Misfire (1986)

In 1986, Arby’s tried a bold repositioning with “We Have the Meats,” aiming to spotlight its roast-beef heritage. TV spots showcased mountains of sliced meats, daring competitors to match up. But the heavy-handed approach felt tone-deaf amid growing health consciousness and the low-fat diet craze. Many viewers found the endless salami stacks more grotesque than appetizing.

Sales stagnated, and consumer surveys revealed that while potatoes and curly fries resonated, piled-high deli visuals did not. Arby’s scaled back the campaign and refocused on sandwiches and targeted promotions. Marketing analysts now cite this flop as an example of misreading cultural trends. Flaunting excess when moderation was in vogue sent the wrong message. Today’s Arby’s ads balance indulgence with quality messaging, a nod to lessons learned from the meaty misfire.

9. Wendy’s “Where’s the Fish?” (1985)

Riding the success of “Where’s the Beef?”, Wendy’s rolled out “Where’s the Fish?” to launch its new fish sandwich. They replicated the original’s format, with elderly customers demanding more fish, but the joke fell flat. Audiences saw it as a transparent attempt to recycle old humor rather than introduce fresh appeal.

Within weeks, the campaign was pulled and replaced with straightforward product shots. Experts argue that nostalgia must be balanced with innovation. Reusing a cliché without new context risks alienating loyal customers. Wendy’s quietly shifted to partnerships with pop culture icons and seasonal promotions. They learned the hard way that fishing for attention doesn’t always guarantee a catch.

10. KFC’s “Bucket Lite” (1989)

In 1989, KFC tested “Bucket Lite,” a skinless-chicken option marketed as a healthier twist on the classic bucket. Ads touted fewer calories, and stores offered special displays emphasizing light bone-in pieces. But customers balked. Removing the skin stripped away much of the flavor and texture they loved.

Sales underperformed, and KFC ceased the test within months. Nutritionists now note that brand extensions must honor core product attributes. Tweaking a signature item can undermine authenticity. KFC returned focus to original recipes and portion control messaging instead of radical product surgery. The Bucket Lite experiment endures as a lesson in staying true to what customers expect.

11. Dairy Queen’s “Pretzel Sticks” Tie-In

In 1988, Dairy Queen introduced Pretzel Sticks, served with chili cheese sauce, to boost off-season sales. Though pretzels were trendy at malls, the pairing with DQ’s sweet environment felt awkward. Customers reported soggy bites and confusion over whether they’d ordered dessert or a snack.

After a brief run, the pretzel racks disappeared. Analysts suggest that menu expansion works best when flavor families align. Adding non-dairy items to an ice-cream-centric brand risked diluting DQ’s core identity. Today, Dairy Queen tests limited-time flavors more carefully and partners with known snack brands, avoiding mismatched menus.

12. Jack in the Box’s “Extreme Salad Bar” (1987)

Jack in the Box launched an “Extreme Salad Bar” to counter fast-food stereotypes. The bar boasted dozens of toppings and dressings, but customers used to quick service balked at the self-serve hassle. Long lines and cross-contamination worries surfaced, and health inspectors flagged maintenance issues.

By year’s end, the salad bar was scrapped. Industry experts now stress that quick-service chains should avoid complicated add-ons that slow down operations. Jack in the Box refocused on core sandwiches and streamlined sides, leaving the “extreme” idea behind.

13. Subway’s “Bread Stick Bread” (1989)

In 1989, Subway offered “Bread Stick Bread,” loaves shaped like giant breadsticks for sandwich building. The novelty attracted curiosity, but customers found the extra crust unwieldy and difficult to eat. Sales dropped sharply after the first week.

Subway learned that practical usability trumps gimmicks. Innovations must enhance, not complicate, the core experience. Since then, Subway’s R&D has focused on subtle flavor tweaks and ingredient sourcing, steering clear of over-engineered bread concepts.

14. Hardee’s “Frisco Burger” Rehash (1986)

Hardee’s tried to reclaim market share by reintroducing the Frisco Burger, once a local favorite, as a national item. Ads touted melted Swiss cheese on sourdough bread, but supply inconsistencies led to stale buns and uneven cheese melts. Customers expecting consistent quality were disappointed.

Hardee’s quietly rolled back the reintroduction. The flop highlights how operational challenges can doom even beloved items. Today, chains pilot regional classics in test markets before nationwide rollouts to avoid similar brand damage.